- Home

- G Scott Huggins

The Girl Who Wasn't There

The Girl Who Wasn't There Read online

The Girl Who Wasn’t There

Moon 2095 (Book 1)

G. Scott Huggins

Copyright © 2019 G. Scott Huggins and Michael A. Wills

Published July 2019 Digital Fiction Publishing Corp.

All rights reserved. 1st Edition

ISBN-13 (paperback): 978-1-989414-34-7

ISBN-13 (e-book): 978-1-989414-35-4

This one is for my children, Tristan, Cora, and Briona, because it’s the first thing I’ve written that they can read before they are teenagers without scarring them for life.

Contents

Contents

Chapter 1 The Face in the Window

Chapter 2 A Deadly Light

Chapter 3 Constable Mom

Chapter 4 Being Schooled

Chapter 5 The Regulations of Robotics

Chapter 6 Pieces of the Past

Chapter 7 A Walk Through Ocean Desert

Chapter 8 Captive Bound and Double-Ironed

Chapter 9 The Girl Who Was There All Along

Chapter 10 Moments of Truth, Days of Hope

Thank You!

Also by Digital Fiction

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter 1

The Face in the Window

Jael gritted her teeth on a scream of frustration as she flew in a semicircle through the air. Twisting, she just managed to get her arms in front of her before she was slammed into the soft rubber mat. The impact slammed her crutches into her forearms with stinging force and drove her breath from her lungs. Her face bounced off the floor, burning with pain.

“I told you not to try that double kick,” Master Balogun said.

Jael rolled painfully onto her back, tasting blood on her lips. She blinked tears away furiously, looking at her sensei. His ebony face was clean-shaven and set like a granite statue, lips compressed in a line. He stood over her like a disapproving god.

Jael’s brows drew down in a scowl. “I thought you were supposed to be teaching me,” she said, hating the whine that tinged her voice.

He said nothing, but raised his eyebrows.

“Sensei,” she added too late, feeling the blood rush to her face.

“Don’t address me from the floor,” he said, voice flat.

Jael gripped her crutches and spun around, levering herself up on them and pushing up with both legs. Too far. She lost contact with the floor and nearly fell in the Moon’s weak gravity.

“I am teaching you, young lady,” Master Balogun said, “and that includes what you cannot do as well as what you can.”

Jael’s eyes widened in shock, and she snarled silently.

“Tcha!” Her sensei let out an exasperated puff of air. “I do not mean with these.” His foot flashed forward and tapped her legs. “Every time I talk about what you can’t do, you think I mean your disability. I’m talking about what you’ve learned. About your technique. I know your legs are strong, whether you can walk with them or not. But you have not learned enough, not practiced enough, to use that strength yet.”

Jael’s face burned. She had tried so hard to prove him wrong. She had thought that rising up on her crutches and kicking out with her legs would catch him by surprise. Instead, Master Balogun had caught her effortlessly by the ankles and swung her over his head like a sledgehammer. Neither move would have worked on Earth, but in Luna’s one-sixth gravity, even master martial artists were still learning the limits of the possible.

Even so, Master Balogun was still far ahead of her. He continued. “Instead of playing to your strengths, the balance and precision you have learned with your arms and tonfa, you keep trying to bulldoze over your weaknesses, as though you can beat them into submission. That is not the way the Art works. Now since you seem so in love with building up strength, go do some push-ups under real weight and show me how far you can go.”

Her blood blazed with resentment, but she forced herself to say, “Yes, sensei.” She turned and swung off to the weight racks, already feeling bile climbing up her throat.

They’re crutches, not tonfa, she thought, her eyes locked on the huge vests hanging there. But Master Balogun never permitted her to call them that while she was practicing. They did look somewhat like the thick rods of wood with handles that allowed their wielder to block and swing to strike opponents. But her crutches were aluminum and carbon fiber, at least three times longer than tonfa, with flared cuffs that braced her forearms. She planted them viciously on the mat in front of her and smothered a forbidden word as she vaulted off the mat, flying through the air in a low, uncontrolled jump. Eventually, she landed and swung her legs through her crutches, moving more carefully.

Jael hated the Moon, how it made everything easier in the hardest possible way. Getting around was a lot easier than it had been on Earth, the way she had to lift her body with her arms and swing her legs in front of her. But at least there you could pound on the ground and not fly off balance.

Laboriously, Jael lifted and buckled the weighted vests over her torso, then fitted the weighted sleeves around her arms. She struggled with the cuffs around her thighs, ankles, and knees. She rolled prone, 275 kilograms of lead encasing her. She now weighed about what she had on Earth: 123 pounds.

On the moon, where gravity was only one-sixth as strong as Earth’s, the human body would lose muscle mass if it wasn’t regularly exercised. Fortunately, that health problem wasn’t nearly as bad as the ones that plagued humans who lived in true microgravity on space stations or asteroid colonies. But while those places could spin large habitat rings for constant gravity, all the way up to Earth’s normal one-gee, the Moon couldn’t. The Moon’s rather cumbersome answer was the weight vests.

Jael reversed her crutches and gripped the handles. Setting the rubber tips atop the cuffs on the floor, she began the push-ups that her sensei had ordered. Slowly.

Mass was not weight. The lead weights that pulled at her did not remind her at all of how she had felt on Earth. One. Two. They made her work harder to overcome their greater inertia. Four. Five. This was Master Balogun’s favorite test of her endurance and precision, the precision she would never have in her legs. She snapped open her eyes and glared at him. Seven. Eight.

I don’t mean your disability, he’d said. Only he does, they all do, they always do, she thought. Her stomach twisted at the thought. It was why she couldn’t fight the way she wanted to. Fifteen. Maybe. Or seventeen. Damn. It was why their family was on the Moon at all, and Mother and Dad thought she didn’t know it. So her life could be a little easier, and so she could be a little more capable. Just never capable enough. She heaved up again, and sank down, the weights beneath her digging into her stomach.

Master Balogun looked down at her. “Thirty push-ups. No shame,” he said evenly. “But nothing commendable, either. I can teach you nothing more today. Go and find peace in something else for today.”

Jael felt her blood racing with more than the physical exertion as she swung herself over to the lavatories and washed her mouth out. No shame. What did he know about shame? No one stared at him just for walking past them. No one thought of him as dead weight, more useless than the stupid vests.

Having nowhere better to go, and no one else to talk to, Jael turned toward the antechamber of the ballistics range. She thought about jumping there in a long arc, but while her legs were powerful enough to make the leap, she didn’t want to risk Master Balogun’s disapproving stare, either.

Only little kids jump everywhere just because they can, she thought. One more little joy of life that everyone seemed determined to take from her.

The wide door of the range slid open, admitting her to an antechamber with gray-brown walls. A Secutor stood behind the cou

nter, between her and a rack containing a dozen varieties of weapons. The Secutor looked roughly like a kneeling humanoid: a polymer-armored torso with two articulated arms and a featureless head. From the waist down, its thighs angled toward the floor where it “knelt” on its treads. It could stand and walk or climb, but just now its “feet” were folded up and over its tread-housings.

“Let me have a coilgun,” she snapped, relieved not to have to be polite. “Long barrel, semi-auto.”

The Secutor’s black ovoid head regarded her. “The range is occupied,” it said.

“I know the range is occupied, you worthless piece of rejected factory trash!” She curled her lip in contempt. “My brother’s in there. Now give me the gun and ask him to let me in to join him!”

“Coilguns cannot be dispensed until entry is imminent,” replied the Secutor, with programmed equanimity. “Complying with request transmission.”

“Sync range scenario with my convirscer,” Jael commanded. She withdrew the flat, glassy screen. “Varpal view,” she said to it. Immediately, the convirscer’s leaf-thin earpieces unfolded, and the screen itself became transparent.

“Complying.” The lights went down in the antechamber while Jael’s convirscer showed her the virtual augmented roleplay of Paul’s scenario. The wall containing the door to the range proper vanished out of existence. Suddenly, her brother was facing her, staring through his own convirscer. He leveled his coilgun at her head. Looking right through her, he fired.

Jael stifled a shriek and flinched, then blew out an exasperated sigh. Of course, Paul hadn’t been shooting at her. A shadowy flicker of motion slid in front of her brother. An Aidrone. The tiny hexjet flyer slid to one side, but her brother snapped off three more shots, and the hologram of the Aidrone staggered in the air, “crashing” to the floor. He whirled as two more Aidrones whizzed in from his flanks, firing steadily. In front of him, a larger Spidrone emerged from a rip in the floor, its multijointed legs making Jael shudder. The monstrosity drew his fire, its heavier weapons forcing him to react. The Aidrone fliers got their own shots off, and blood bloomed on his clothes. Jael swallowed in distaste. The wounds and wardroids certainly looked real through the convirscer.

Paul pronounced a word that Jael could not hear but which was certainly on the Mother-Disapproved Language List. Then he cocked his head and addressed the ceiling. The projections disappeared, and the range lit up.

“Paul Wardhey grants access to Jael Wardhey,” said the Secutor. It swiveled at its waist and detached a long-barreled coilgun, examined it, and handed it to her along with a flechette magazine. Carefully, with the ease of long practice, Jael inspected her gun. Keeping her finger away from the trigger, she entered the range, a featureless dome over a wide, cylindrical chamber.

“Hey, sis,” her brother said. His red-blond hair was sweat-matted, and his pale eyebrows drew down. “What’s up with you that you need to interrupt my AI-War campaign?”

“Sorry,” she growled. She wasn’t sorry at all, but she knew she should be. It was rare enough for Paul to get the range entirely to himself, which was the only time he could run his AI-War game. She didn’t feel like apologizing, so she said, “I don’t know why you always want to play AI-War scenarios, anyway. It’s creepy.” That was true. It was bad enough that the AI-War had ever happened. The thought of it happening again chilled her bones.

“Well, if we ever have to do this for real,” he said, tapping his gun, “it’s the best way to practice.” He looked at her. “Sensei kicked you out, didn’t he?”

“Shut up,” she mumbled.

He shrugged. “Reset for standard practice. Simulated targets, fifty meters.”

Jael let her right-hand crutch fall and stood as straight as she could, presenting her side to the target, bracing herself on her left crutch. The flechette-throwing coilguns produced very little recoil, but what there was could still throw her off-balance, since she had almost no ability to move her legs independently of each other.

Through their convirscers, the range went dark, and two silhouettes materialized in front of the smooth, armorgel walls. Jael briefly wished that there was some way they could both run through a Danger Room scenario, but the coilguns were loaded with real flechettes, and playing around with them where you could hit another person was needlessly dangerous. The scenarios were only for lone practitioners. There was no fear of ricochets or penetrating the walls of the hab. Metal was cheap on the Moon, and the range was clad in a double thickness of foamed titanium, layered with graphene.

On the other hand, Jael was glad enough to have an excuse not to play through Paul’s AI-War scenarios. Something more historical and less frightening, like World War II, would have been interesting, though.

Of course, she couldn’t do the legwork that would allow her to score decently. But simple target shooting was well within her capabilities.

“Range clear,” said the synthetic voice of the Secutor.

Jael raised her gun, sighted along its open-work barrel and sent five 1.5-millimeter needles streaming toward her target with whisper-cracks of sound as they went supersonic. She waited for the score.

“Ten. Ten. Ten,” the voice repeated. “Nine. Nine.”

Over it, she heard Paul’s score. “Ten. Nine. Ten. Ten. Ten.”

Her brother looked over at her, face carefully blank.

“What?” she snapped.

“You told me to shut up,” he said.

“Sensei never lets me try anything I want to do!” she said, unable to keep the bitterness out of her tone.

“That’s because you keep wanting to fight him.”

“That’s what he’s supposed to be training us to do!”

“No.” Paul shook his head with the same maddening calm that he shared with their father. “He’s supposed to be training us to fight.”

“That’s what I said!”

“But it’s not what I said. I said you want to fight him. He’s training you not to do that, and he has to get you to listen. Instead, you get mad. Then you shut him out. Then you lash out. Then he takes you to the mat. And then he throws you out. And you end up here, with me outshooting you because you’re shooting mad instead of shooting calm. And we both know that’s not usually how it goes.”

Jael took a deep breath and crushed her anger with all her strength. Somehow, Paul calmed her down rather than making her angrier. “I know I shouldn’t, but why won’t he ever at least let me try things my way?”

Her brother snorted. “He is. He just showed you why your way won’t work.”

Jael glared at him, but Paul only cocked his head. “Oh, come on, do you think sensei couldn’t completely stop you if he wanted to? You’re just trying his patience.”

“I just want him to show me how to do it my way so it will work,” she said softly.

Paul turned to face her. “And why is that so different than him showing you things he knows will work?”

She dropped her eyes. She didn’t know why it made such a difference. But it did.

“You calm, now?” he asked. “Or am I going to embarrass you again?”

“Let’s see if you can.” She raised her pistol. This time, she exhaled and pressed the trigger to the limit of its slack, squeezing it as her mother had trained her, not snapping it backward. “Ten. Ten. Ten. Ten. Ten,” recorded the Secutor. Paul was doing the same, until the final shot. “Eight,” the computer said.

“Eight?” asked Jael.

“Well, you’re using that great long barrel, you ought to be scoring higher.”

“I want to work off some frustrations. Spar?”

“Are you going to fight the way you’re supposed to? Seriously. You’re not working off your frustrations on my head.”

“I promise,” Jael said, meaning it.

They returned their guns and walked out to the surface of the great dome of Thunderhead’s gymnasium. The sparring mats leaned against one of the outer walls, near an airlock. Low-set, thick portholes gave a punctu

ated view of the lunar surface, currently bright with daylight.

They removed their convirscers. The COmmNet VIRtualScope Encyclopedias were sturdy but too useful to risk in a stupid sparring accident. Paul took a red belt from a pocket of his outsuit and wrapped it around his waist. Jael had not bothered to remove her purple one. Paul began stretching.

“I sure do miss my gi,” he said, referring to the loose jacket and pants that martial artists wore on Earth.

“I don’t,” Jael said. One more change of clothes to get in and out of, and then to lug around. Then, because she almost never got to, she smiled and said, “Outsuits are always required. That’s regulations.”

“This is the dumbest place in all of Thunderhead for that regulation to apply,” Paul said. “This is supposed to be the emergency shelter for the whole colony. One gigantic blockhouse right next to the landing pads for emergency evacuation. If anything breaches this, our outsuits wouldn’t do us any more good than wearing a nice thick coating of sunscreen.”

Jael tsked at him, regardless of the fact that she completely agreed. But they both knew that the regulation made sense most of the time and would no more have thought of disobeying it than they would have of parading around completely naked. Everyone wore an outsuit, the deceptively thin garment that covered them from ankle to wrist to neck. Jael spoke into the microphone set into her collar. “Full-contact routine.”

Her outsuit swelled outward at her forearms and lower legs, providing the necessary padding. Her shoes reacted similarly and sealed to her ankles. She flipped her hood up and felt the flowing material mold itself around her forehead and ears to protect her, then caught her crutches before the Moon’s gravity could topple them.

In the case of a pressure blowout, the suit’s hood would become a full-blown helmet, sealing to both her neck and the gloves in her pocket as fast as she could put them on. The air reservoir on her back would keep her alive for thirty minutes, or more if she could reach an actual air tank.

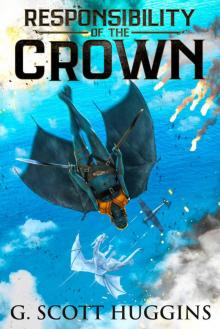

Responsibility of the Crown

Responsibility of the Crown The Girl Who Wasn't There

The Girl Who Wasn't There